| |

|

|

|

|

1940, Lourdes

We were so rundown that even if sleep was imperfect,

a roof over our heads seemed like a heavenly invention.

After weeks in the same clothes, unable to wash properly,

much less to bathe, we buried our vanity and lapsed

into general indifference.

On the first morning there Werfel went to get a shave,

and I went for a stroll along the bookstalls. I found

a small book on the little saint of Lourdes and felt

that, since we were there now, we ought to know her.

I gave Werfel the book with the remark that this was

something extraordinary, and he read it with a great

deal of interest.

As time went by, I also bought all the devotional tracts

about Saint Bernadette. Her grotto at Massabieille made

a deep impression on us; with all due emotion we bravely

drank the water from her spring, waiting for some stroke

of luck to help us to get out of town. We were imprisoned

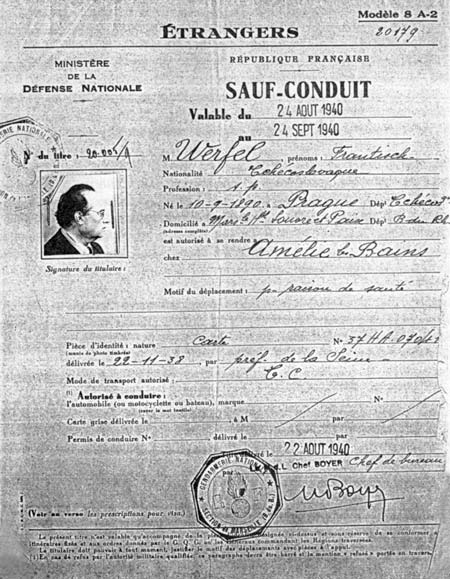

in Lourdes, as in all of France; we not only needed

visas to get out of the country but safe-conducts from

the authorities to go from one village to the next.

I do not know how many hours we spent at the police

station of Lourdes, trying to wangle those precious

slips from the men whose precursors in office had harassed

the child Bernadette.

|

|

|

I wrote in my diary:

Franz Werfel's possible rescue, my rescue - everything

lies in a clouded future that we know nothing about.

The grotto of Lourdes has a healing effect on our souls

while we are here; once we go away, this effect will

cease, and our hearts will be burdened again ...

What matters, if I understand it right, is to cast

out the galling criticism in ourselves. Today I was

twice at the grotto - to morning Mass, and to an afternoon

service with a sermon, music, and innumerable little

Bernadettes (costumewise, at least). Suddenly I was

so moved I had to cry and hide my face. It tore at my

heart-strings for no visible reason - and that is what

matters!'

After two weeks at our Hôtel Vatican we were

moved into a better room with - thank God! – twin

beds. Two more weeks passed, and the post office advised

us of the arrival of our suitcases, which we had left

in the ditch at Saint-Jean-de-Luz, with the chauffeur's

wife. We felt enriched, though not much so. Meanwhile,

the hotel manager, whom we had told of our lost trunks,

remembered knowing a friend of the Bordeaux station

master. He wrote letter after letter, but got no reply

as long as we were in Lourdes.

On 3 August we finally got our safe-conducts back to

Marseille. With troop trains shuttling incessantly between

the occupied and unoccupied zones, there had been no

civilian rail travel in three weeks, and we were more

or less the first to venture it. Once again, God's staging

was perfect, with the heat near the boiling point. Food

parcels with white bread, ham, hard boiled eggs, and

pastry were tied with string and stowed in the horse-drawn

cab with our few pieces of hand luggage. We rode out

of the Avénue de la Grotte, passing all the little

bistros and, the post office on our way to the station,

where we had to stand at the ticket gate for two hours

before the train carried us off through the green mountain

country.

It was dark by the time reached Toulouse, where we were

greeted by a stench of army boots and Armageddon. Senegalese

soldiers lay sprawling on the tracks, fast asleep. We

settled down in the grimy station restaurant and began

to eat enormously, for no reason at all. There are no

adjectives to describe the sanitary facilities at that

railway station. The restaurant closed at ten. Ejected

from its hospitable premises, the four of us, the Kahlers,

Werfel, and I, sat on the platform on our suitcases,

faithfully playing our parts in this supercolossal spectacular,

'World's End', until a train left for Marseille at dawn.

> top

Marseille

The Cannebière was sun-baked early in the morning.

We walked from the station, carrying our suitcases ourselves.

In front of the Hôtel de Louvre et de la Paix

six brand-new cars stood gleaming in the sun,- a long

time had passed since we had seen a polished, shiny

car. In the lobby we saw officers in field grey, with

pistols and shaved heads. The Germans were in Marseille!

Our old friend the hotel manager told us under his

breath that the German commission was going to leave

in two hours; in the meantime we should use the rear

lift and stay in our rooms. Had we spent seven weeks

on this 'Tour de France” as Werfel termed our flight

from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic and back, only

to run right here into the jaws of the Germans?

The next few weeks in Marseille were unbearable. Daily

there were new rumours, every week a new commission

to plunder and ship stocks of supplies to Germany -

rice, noodles, oil, sugar, and so forth.

Hunger had come to Marseille in our absence. It was

a poor city to which we returned: food was scarce and

bad, soap and fat virtually unobtainable, butter a memory.

And the daily pilgrimages to the consuls, where those

gentlemen would let everyone feel their full power!

The city swarmed with refugees. They had been Germans,

Austrians, Czechs, Poles; now most of them were stateless,

many without passports, some without any papers, all

wanting only to get out, to go far away. "Far from

where?' was a joke of those days, when it seemed likely

that Hitler would conquer the world.

Werfel was unnerved by the confusing rumours he brought

daily from the Czech consulate. The armistice signed

by the French obliged them to 'surrender on demand'

all Germans (which then meant also all former Austrians

and Czechs) named by the German Government. Werfel would

hear from someone that he was 'first on the list', and

would collapse in tears. I thanked God for letting me

keep my head, at least, so I could calm him.

Despite our own fears we saw many others in the same

distress. They helped to distract us from our troubles.

Werfel's name was not supposed to be mentioned, but

some refugees kept shouting it over the telephone: "Good

morning, Herr Werfel! I can't tell you my name...”

The telephone was in the lobby of our hotel, where

everyone could hear it. For a while the Gestapo occupied

rooms on our floor; when they came, we were warned by

the manager to keep out of sight. He would not let them

see the hotel register, either.

When we did not have to stand in line at some consulate,

we would take a cab out to the beach. There the sea

gulls screamed, the salty smell of the haze over the

water carried far, and good ideas came to mind. In those

blessed hours we forgot that there was evil in the world,

lying in wait for us.

> top

Flight

The French had promised us exit visas, but when time

passed we did not get them, any more than others did,

we began to think leaving without them. Crazy escape

plans were hatched. One - to travel to a small border

village, spend the night there, sneak up to a cemetery

at 5 a.m. and meet someone who would be waiting behind

a shack and would smuggle us through the cemetery and

across the border - was rejected as too vague. Another

plan was to seize a ship, man it with Czech refugees,

and dress it up as a Red Cross vessel, with me as head

nurse.

|

|

|

Werfel's Czech passport

Werfel's Czech passport records in detail his efforts

to secure departure from France: first of all, the first

US visa is entered, issued in Marseilles on 14 October

1938; then there is a French exit permit for travel to

Portugal via Spain using the Hendaye border crossing,

issued in Bayonne on 23 June 1940 (neither of these could

be used); next, there is a Portuguese transit visa for

travel to the USA, issued in Marseilles on 7 August 1940,

to be used within 30 days (expired), plus a Spanish transit

permit to Portugal issued in Marseilles on 8 August 1940,

a Portuguese transit visa, issued in Marseilles on 31

August 1940, an entry permit for Mexico, issued in Marseilles

on 27 August 1940, a stamp from the "Nea Hellas"

dated 4 October 1940, and the second entry visa for the

USA dated 22 March 1941 from Nogales on the Mexican border,

further to which, on 18 June, Werfel received his "first

papers" for the US naturalization procedure. |

|

There was talk of a man being sent from America especially

to help us all. We waited; the man did not come. But

what came one day, out of the blue, alone, orphaned

and tattered, was my little trunk with the scores of

Gustav Mahler´s symphonies and Bruckner´s

Third! The efforts of our kindly host in Lourdes had

not been completely in vain, and I did not mind losing

the rest of our possessions as long as I had what was

most important to me.

A telegram carne from New York, advising us that our

American visas had been cabled to the American consul

in Marseille. The taxi ride to the consulate cost a

small fortune. The waiting room was full of excited

people; once again we sat around for hours, and when

we got to see the consul, he knew nothing of a cable.

It was only at our vigorous insistence that he managed

to locate it.

No ships were sailing from French ports, and to embark

for the United States in Lisbon, you needed Spanish

and Portuguese transit visas. With the American visa

in a Czech passport like ours there was no trouble about

getting them; you just had to wait your turn. The refugees

stood in line before the consulates from sunrise until

closing time, if they did not faint in the glistening

heat or leave, to keep from fainting. A man with Werfel's

heart could die on the spot. But all applicants had

to appear in person.

At the Spanish consulate I bribed the doorman to take

our card in, and we were promptly called up out of turn

and issued visas. I tried this on the Portuguese doorman,

too, but there it did not work; the man returned the

card to me as undeliverable. We went to the end of the

line. It inched forward with maddening slowness. At

high noon the pavement seemed to melt under our feet.

Werfel kept mopping his brow. His eyes burned in his

dripping face; he suddenly looked ashen. I was desperate

and ready to give up when a young Austrian acquaintance

of ours approached. 'That's impossible,' she said indignantly.

'Why should Franz Werfel stand in line like this?"

We knew Hertha Pauli from Vienna, where she had been

one of Paul Zsolnay´s promising authors, and had

met her again in Paris and recently in Lourdes. She

had just happened to pass by; she could not hope for

a visa herself, because she had no passport. I explained

to her that our card had failed to go through. 'Wait

a minute,' she said, and disappeared.

|

|

|

| Franz Werfel's laissez-passer,

valid for one month (25 August to 24 September 1940) |

|

In two minutes she was back beaming. 'Come,' she said.

'You’ll have to sit down, first of all. The consul

expects you at four.’ I really had to sit down.

Werfel kept mopping his brow. 'How did you manage that?'

I asked. 'I called up,' she said simply. 'When I mentioned

your name the consul came right to the phone. He is

an old admirer of yours,’ she told Franz Werfel.

Then she turned back to me. 'l hope you’ll forgive

me but I had to call as Madame Werfel.' We laughed aloud,

for the first time in weeks, and headed for nearest

bistro. 'That calls for champagne,' I declared.

Punctually at 4 p.m. we got the visas. In exchange,

Werfel had only to autograph the consul's Portuguese

edition of Musa Dagh. (Subsequently, through the Czech

consul, an angel of a man, Werfel got Czech passports

for a score of stateless refugees, including Hertha

Pauli, who had aided us.)

Soon after we got our visas, the much-talked-about

American came to Marseille. He was Varian Fry, the representative

of the Emergency Rescue Committee, which had been formed

in New York for the purpose of bringing the political

and intellectual refugees of unoccupied France before

the Germans got them. Mr. Fry did the job, but his laconic

manner and expressionless face made him appear to be

doing it gruffly and grudgingly. He came to our hotel,

had dinner with us, and then dragged out our departure

for two more weeks in a wild-goose chase after a ship.

This, of course, fell through, and on 11 September he

finally told us to be ready to leave by rail the next

morning at five, together with Heinrich Mann and his

wife and nephew Thomas Mann's son Golo.

There was no time to lose. From Mr. Fry's hotel we

rushed back to ours, where Werfel burned all his writings

and drafts in a small ash tray while I was busy packing

- for, as by a miracle, the rest of our lost luggage

had also caught up with us. Our friend Frau Meier-Graefe

stayed up with me all night until it was time to leave.

Mr. Fry and another young American got on the train

with us. In Perpignan we waited several hours for another

train, which took us to the border town of Cerbére

by nightfall. The two Americans hoped that our American

visas would get us through on the train, even without

French exit visas. This gambit failed, unfortunately,

so we took rooms at an otherwise deserted inn and waited

for orders.

In the morning I rose early. Unable to stand it long

at the eerie empty inn, I went to the station, where

we had arranged to meet. There was no breakfast to be

had, just tea. We held a war council. The police, the

Americans told us, had repeated their refusal to let

us cross the border on the train, so we came to the

decision to try on foot although Heinrich Mann was seventy

and Werfel had a heart ailment.

Mr. Fry, the only possessor of an exit visa, would go

on the train with the luggage and await us at the Spanish

border town of Port Bou, while his young colleague would

guide us over the hills. We had to go soon - the Spanish

sun was infernally hot at six o'clock already - but

Golo, usually a most reliable young man, was nowhere

to be found. Two valuable hours passed before he came

back, refreshed, from a swim in the Mediterranean and

we could set out to climb the Pyrenees.

In the village it suddenly struck Nelly Mann that it

was Friday, the thirteenth. She wanted to turn back.

Werfel and I walked ahead, to put an end to the hysterical

squabble; we were supposed, after all, to be innocent

excursionists. The village scarcely lay behind us when

the young American turned off the road and uphill, on

a steep, stony trail that soon vanished altogether.

It was sheer slippery terrain that we crawled up, bounded

by precipices. Mountain goats could hardly have kept

their footing on the glassy, shimmering slate. If you

skidded, there was nothing but thistles to hold on to.

After a two-hour climb the youth bade us farewell and

hurried back to show this "road' to the Manns.

We stood alone on the mountaintop. In the distance we

saw a hut shining white on the white rock. This was

the Spanish border post, where we were to present ourselves.

Laboriously we crawled downhill; trembling, we knocked

on the door, which was opened by a dull-faced Catalan

soldier who knew Spanish only. His understanding was

somewhat improved by the packets of cigarettes we slipped

into his pocket. He grew friendlier and motioned to

us to follow him. At last we could walk on a passable

road - but where was this idiot taking us? Back to the

French border post!

We were brought before an officer. I was wearing old

sandals and lugging a bag that contained the rest of

our money, my jewels, and the score of Bruckner's Third.

We must have looked pretty decrepit, surely less picturesque

than the stage smugglers in Carmen. After the march

in the broiling sun we felt utterly wretched. In a sudden

burst of kindliness, the officer waved us through.

Tired, perspiring, we unsteadily retraced our steps,

clambered over the dramatic iron chains that separate

France from Spain, and continued our descent after the

soldier had telephoned down to the custom-house. On

the road I found half a horseshoe and picked it up;

we took it for a good omen and walked more cheerfully.

It had grown late in the day. The heat was unimaginable.

In Port Bou we did not see any officials; they were

probably taking their siesta. But the custom-house porters

- whom we had approached with deference at first, mistaking

them for Government functionaries - were oddly amiable,

promised us good luck, brought wine, and cursed Franco

and Mussolini. Catalonia was apparently still anti-fascist,

and we took courage in spite of our great weariness.

At last, our travel companions arrived. We pretended

to be mere casual acquaintances, though I hastily whispered

to Golo to tip the porters, who had already been discussing

the fact that there was a son of Thomas Mann in our

group. When we had given them virtually all our French

francs, they could not do enough for us, telephoned

for the best rooms in town, and fought over our bags

when we were finally summoned to the custom-house.

Then came the dreaded moment: the passport control.

And, as always, it turned out that the really dangerous

situations have to be faced quite alone. There was no

American in sight, no one to help.

Like poor sinners we sat in a row on a narrow bench

while papers were checked against a card index. Heinrich

Mann, greatly endangered because of his leftist tendencies,

was travelling with false papers, under the name of

Heinrich Ludwig; Werfel, travelling under his own name,

had heard in Marseille that Hitler himself had put a

price on his head; Golo Mann was in danger as his father’s

son. Yet Golo sat quite calmly reading a book, as if

the whole business did not concern him. Nelly Mann had

half carried her aged husband over the thistly mountainside,

and her stockings hung in shreds from bleeding calves.

After an agonizing wait we all got our papers back,

properly stamped, and were free to continue through

Spain. When I think how many killed themselves up there

on the hill or landed in Spanish jails, I see how lucky

we were to have our American scraps of paper honoured

by the officials at Port Bou.

Discharged, we found Mr. Fry, who had our luggage,

and in gathering dusk we walked together to the hotel

where the porters had reserved rooms for us. It had

been almost completely bombed out in the civil war;

only a primitive dining-room and three or four shabby

bedrooms were still standing. The house looked like

all of Spain, like one bleeding wound. Late that evening

the mayor of the town performed a marriage ceremony

in the dining room of the hotel, because the courthouse,

also, had been pulverized.

We slept as if never to awaken. Then, with a shock,

we were aroused at 4 a.m., for at six our train was

to leave. I still do not know why all trains throughout

our flight always left between three and six in the

morning.

> top

Lisbon

We rattled to Barcelona, a war-devastated, starved,

impoverished city that must have been beautiful once.

In the afternoon Werfel and I sat before a café,

and poor children licked the melted ice-cream off our

plates. We paid with tattered old stamps. Everything

was crumbling and desolate. But we began to breathe

easier in the two days we spent in Barcelona, waiting

for the first plane on which two seats to Lisbon were

to be had. The seats went to the Heinrich Manns, as

the most endangered, and we, with Golo Mann and Mr.

Fry, travelled fifteen hours by rail to Madrid, once

more jammed eight in a compartment.

|

|

|

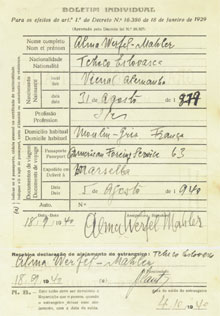

| Alma and Franz Werfel's

registration form for the Grande Hotel d'Italia Estoril

dated 18 September 1940. They are both recorded as having

"Czechoslovak" nationality. It is interesting

to note that here, exceptionally, Alma signed her name

as "Alma Werfel-Mahler" and not - as otherwise

her whole life long - "Alma Mahler-Werfel".

As reference documents, both used travel papers from the

American Foreign Service. They left the hotel on 18 October

1940. |

|

| >

Detail View |

|

|

|

|

|

From Madrid, Werfel and I flew to Lisbon. It was evening

when we landed there at a new, unfinished, unlighted

airport; as everywhere, we were kept standing around,

senselessly, for hours. The passport examiner scrutinized

a list of Werfel's works which had been added to a letter

of recommendation by the Duke of Württemberg, a

high-ranking cleric. When he came to the title Paul

Among the Jews, the official frowned. "I see -

you're of Jewish descent?”

Werfel did not say yes or no. In his confusion he merely

pointed at me, and the official sneered, as if to indicate

that Werfel's descent was obvious to everyone. Then

he gave us the stamp that meant admission to Portugal.

I can never forget those first days of paradisiacal

peace in a paradisiacal country, after the torment of

the previous months!

|

|

|

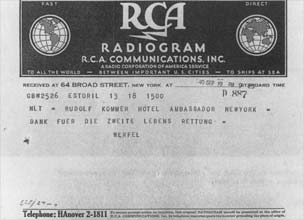

"Thank you for saving my life a second time"

- telegram written by Franz Werfel in Estoril to

Rudolf Kommer, dated 19 September 1940 |

|

|

> top

The "New Hellas”

Two more weeks had to be spent waiting at a hotel near

Lisbon, until we got passage on the Nea Hellas, the

last ship to make a regular run to New York. On the

day of embarkation, when I went to pay our hotel bill,

the clerk seemed to sense that it would leave me short

of cash. "Never mind paying the bill,” he

said. "I’II advance it for you, and you can

send me the money from New York.”

"The kindness of a perfect stranger,” I wrote

in my diary, "has reconciled me with mankind ...”

|

|

|

| The "Nea Hellas", the last

official ship from Lisbon to New York in 1940, bearing

a Greek ensign |

|

The sea was dull. It always is; only the coasts are

interesting, and those only if they are inhabited. We

hardly went on deck. We spent most of the time in our

cabins, reading and talking, took no part in the lifeboat

drills, and wearily dragged ourselves to the shabby

dining-room. On this voyage we were really 'lost to

the world'.

Nothing from outside could touch us. We were overwhelmed

by the pressure of past experiences and the anticipation

of freedom. At sea we heard that the war had come to

Greece. The report proved to be three weeks early, yet

we felt that in all probability our old Greek ship was

making her last crossing. Then we began to get radiograms,

from New York. America was drawing near, and our strength

returned. On 3 January, I94I, Franz Werfel started working.

"Thank God,” I wrote in my diary. "How

wonderful that he can concentrate again! It's Bernadette

churning in his mind ... ”

Five months earlier, on our last day in Lourdes, he

had disappeared for a while. I did not ask where he

had been, but he told me himself. "I’ve made

a vow,” he said frankly. "If we get to America

all right, I’II write a book in honour of Saint

Bernadette."

> top

New York

Since then, the Nea Hellas had brought us safely to

New York. Feeling young and courageous, we disembarked

on I3 October, I940. (Yes, on the thirteenth-!) At last

we set foot on soil that was really free. If I had not

felt embarrassed before the others, I should have kissed

the American earth.

|

|

|

|

|

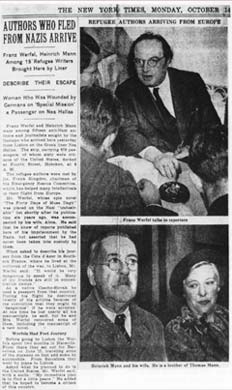

Above: Alma disembarking from the "Nea Hellas"

in Hoboken, New Jersey, on 13 October 1940. Behind

her (partly hidden), Nelly Mann, Heinrich Mann's

wife

Left: Report in the New York Times, 14 October

1940: The refugee authors, including Franz Werfel,

Alfred Polgar, Heinrich and Golo Mann, were interviewed

before they even left the pier. They only gave

a vague description of their escape route, so

as not to endanger those left behind who were

still awaiting rescue.

|

|

|

The landing in New York Harbour was as grandiose an

experience as ever. A mob of friends awaited us on the

pier; all of them were in tears, and so were we. We

spent close to ten weeks in New York - a time of rather

too much commotion, but also of love, friendship, excitement,

and blessed freedom.

Two days after Christmas we left for the West Coast.

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|